the art of sound design

Sound Design. Painting the picture.

The audio medium has always drawn me in, I find it to be a totally immersive and captivating experience that for me far surpasses any visual medium.

When film and TV present a scene it provides a complete ‘picture’, it is a picture painted with all the detail there with very little left to the viewer imagination. When a radio drama paints a picture, it is filled out just enough to set the scene, the place, the atmosphere, but then it leaves the listener to fill in the details from their own experience or imagination.

Close your eyes for just a few moments and listen to your surroundings. There is a plethora of sounds there that when listened carefully to paint a picture of where you are. If you now focus on not only the individual sounds but also their location around you then you can firmly place yourself in that picture.

I realise that not everyone listens to podcasts on a set of high-quality stereo headphones or studio monitors at exactly the optimal positioning. I realise that many will listen through the speaker on a mobile phone or a tablet. I also realise that many will listen on the go with other distractions both visual and auditory. You can still enjoy the story and some of that sound scaping will come though. However, if you do stop to listen with something capable of rendering those sounds with a little more finesse, then there is a whole other world waiting for you.

A few well selected sound effects can transport us from the deck of a sailing ship to deep in the forest, from a busy street café to a domestic kitchen. What colour the sails are or the colour of the kitchen walls is left to the listener to create in their mind, unless of course it is described in the narrative. However, we know we are on the deck of the sailing ship from the sound of the waves, the crack of the sails, the creak of the boards, gulls wheal overhead, voices raised to be heard over the elements. The kitchen is set in our minds with the chink of china, the boiling kettle, the scrape of a chair on tiles and the way voices echo just a little in that space.

A conversation heard from the bathroom will sound very different to a conversation held in the lounge. A conversation held between two rooms will have variances in sound, the husbands brighter voice calling from the bathroom with the echo off hard walls, the wife’s reply from the hall duller with the carpeted floor. Again, a conversation held in a cathedral will sound very different to one held while walking in the woods. The surrounding environment has a sometimes subtle and sometimes dramatic effect. The conversation in the bathroom will have just a little echo as sounds quickly reflect off nearby hard surfaces, the whispered conversation in the Cathedral will noticeably echo over long distance. The woods will deaden any reflections; a distant conversation will lose some of its higher frequencies becoming duller, more muffled.

When starting to look at a scene I picture that scene in my head. Where is it, what does it feel like, what is the mood. I then start to imagine what sounds evoke that location to me, what are the most prominent sounds that the image provokes. These are the Diegetic sounds – the sounds from inside the scene.

There is another layer of sound for the audio drama – the non-diegetic sounds. These are the music that helps to set the tone of the scene, suspense, fear, joy, longing and effects that while not in the scene add to the effect – a heartbeat, a low discordant drone that builds tension. If we hear a swoosh and a clang, then there is a good chance that there is a sword fight. In reality most sword swipes do not create a swoosh sound, however the sound has become synonymous with wielding a sword and that is the picture it paints.

Once I have identified the elements that evoke the feeling of a particular location or mood, I then start to build that soundscape. Choosing a just few sounds integral to the scene to paint that picture. However, that is just the beginning. The sounds can just compete with one another, they can simply sound untrue, even jarring. The trick is to sit those sounds into the scene.

The most useful tools here for me fall into three areas.

EQ – at it’s simplest how thick or thin the sound is, how clear or how muddy the sound is.

Reverb – how much the sound is reflected.

Spatial position – is the sound all around, is it directly ahead, is it to the left, is it close, is it far.

A person speaking close will have a fuller sound than a voice in the distance. A shout in lavishly furnished room will be ‘flat’, a shout in an underpass will echo. A shout in a room will be very directional while a shout in an empty industrial unit will echo around you. This is where using EQ, reverb and spatial positioning set that location in the listener’s mind.

For example, the main character hears a shout from deep inside the abandoned industrial unit. They shout back in reply. For the shout in the distance, I will EQ to thin the sound of voice removing the higher frequencies, muddying it to place it in the distance. The echo will be narrower and placed in the sound field ahead of the listener as the surfaces the voice echoes off are in the distance. The main character’s voice will be fuller being closer, the echo will be wider (the voice and the surfaces the sound bounces back from are much closer), and the echo will spread around the entire soundscape as more surfaces are close to the main character. This is a very simplistic explanation, but it helps to illustrate how altering the frequency range, the echo and how those sounds appear in the field of hearing help to set the scene location and the position of the elements and characters in that scene.

However all we so far have are two echoing voices in a seemingly large space. What turns this space into an abandoned industrial unit? It is now time for the Diegetic sounds. We hear the scrape and grind of a heavy metal door being pushed open, the echoing slam as it slams shut behind us. A sudden flapping of wings as a disturbed pigeon takes to flight its wing beats diminish as it flies off into the distance. Our footsteps echo off hard floor, metal stairs. A chain chinks and clanks from a breeze through a broken window and maybe some water drips and splashed into a pool on the ground. Now our location is set and our characters placed in that industrial unit. Yet we can go further in creating this scene. So far, apart from the shouts there has been no dialogue, so what is the mood of the scene? It’s time for the Non-diegetic sounds. A low synthesiser drone adds a dark mood, more notes layer creating a low discordant sound – now we have tension. A sharp shrill synth note builds above the low drone adding further discordance and a feeling of unease.

We now have set our scene - where the characters are in the space, what that space is and the mood of the piece.

There is an overused saying that ‘it isn’t rocket science’, but it isn’t - although there are lessons to be learned and a skill in knowing how much to add, when and where. Too much sound design can simply overwhelm and confuse distracting from the story. A few well-chosen sounds and time spent placing those elements in the sound field can however lift a scene into something that is totally immersive and believable.

Film is intrinsically prescriptive and, in some ways, a passive experience. It presents a complete picture. You don’t have to imagine anything; it is all presented on a plate. Audio allows and encourages the listener to engage and to create their own interpretations of a scene. Yes, you have set the stage for the kitchen scene, but the listener can decorate that kitchen however they want to. They can personalise the experience. The audio medium is a very personal experience for the reason just touched on, but also because of how it is consumed a lot of the time. For the audience listening through headphones the experience is there, right inside their head. You can’t get any closer or more personal than that.

In truth, the listener should not notice what you have done, all of the little tricks you have pulled out of the bag to create that abandoned industrial unit - they should just unconciously ‘feel’ as though they are there. The role of sound design is to support the story and the dialogue not to stand out apart from it or to compete with it. If the listener just experiences the scene without concentrating on it then - job done.

If I had to condense all of this down into a few sentences then my ethos and approach to sound design is:

Asking myself, what do I hear when I envision the scene. What do I need to do to create that scene without the listener having to consciously think ‘oh, we are in an abandoned warehouse’. They should just accept that they are in an abandoned warehouse. Does what I have created make the story journey more memorable. Does it support and ehance the story or does it compete with it for attention. If it doesn’t make the story more memorable or if it competes for attention then it shouldn’t be there.

My aim is to create the illusion. To put the listener into the same ‘three dimensional’ place as the characters.

Below I have included the tools I use most often when editing and sound designing. While I have more tools for very specific needs, these are always in the edit.

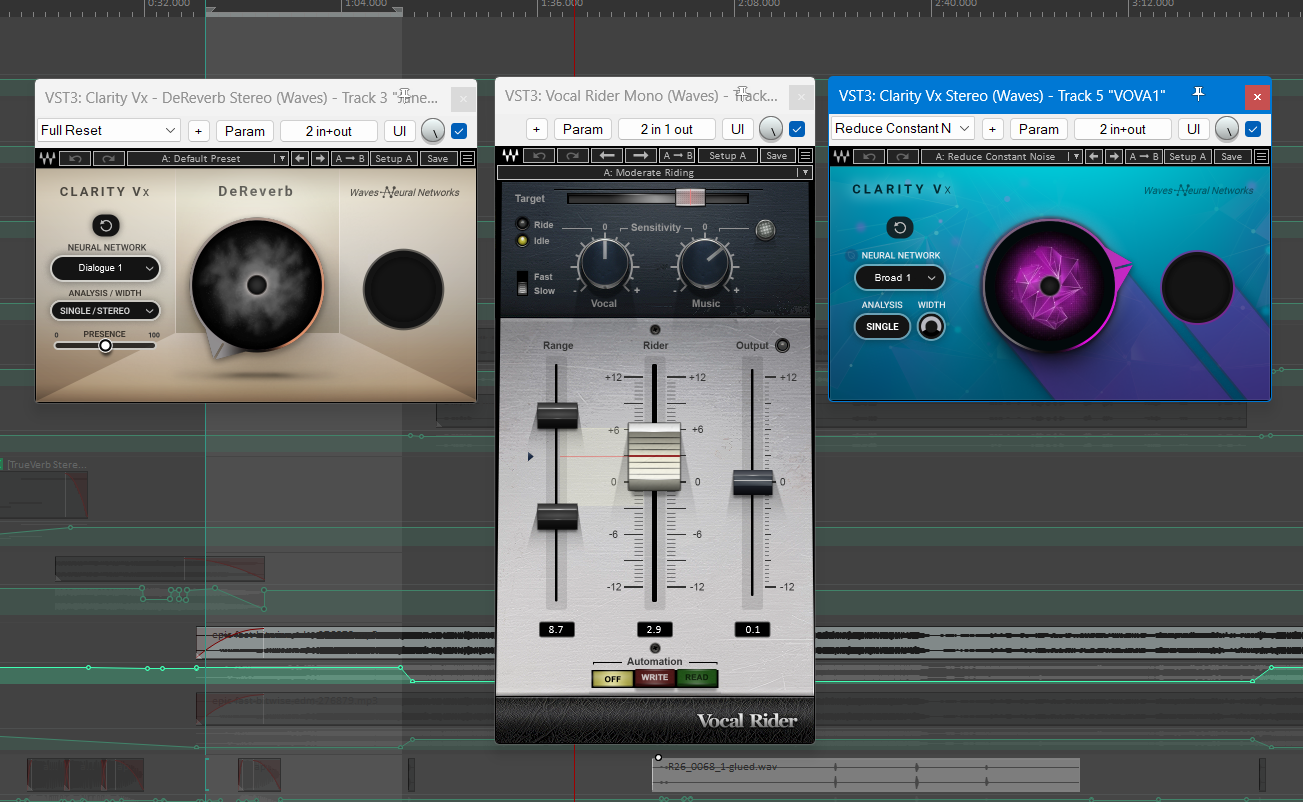

For narration and dialogue: Vocal rider - a real time fader to level out vocals. Clarity Vx DeReverb and Calrity Vx for removing backgound noise and reflections from imperfect recordings.

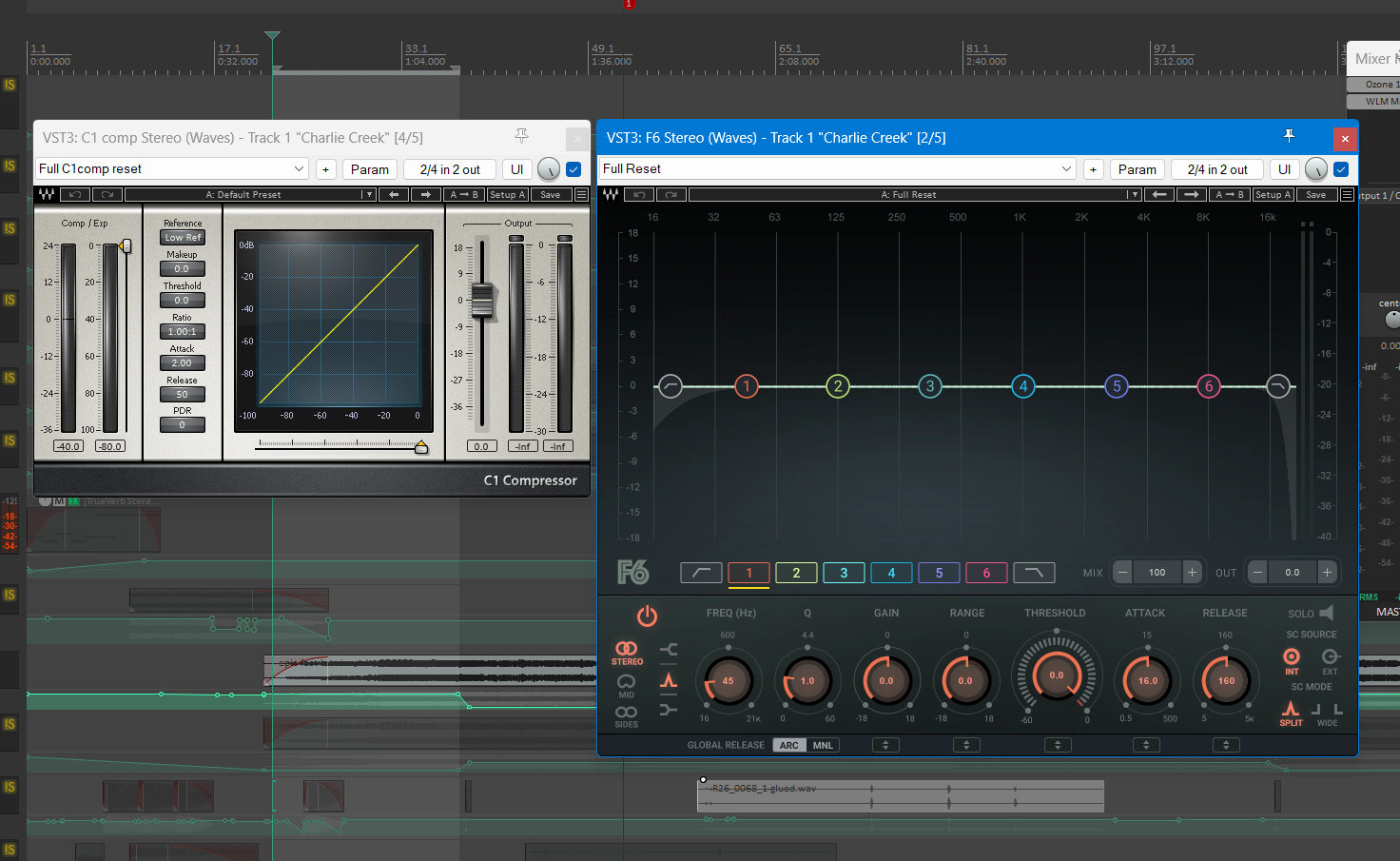

For all elements and especially music and vocals - C1 Compressor and F6 EQ for compressions and EQ as described above.

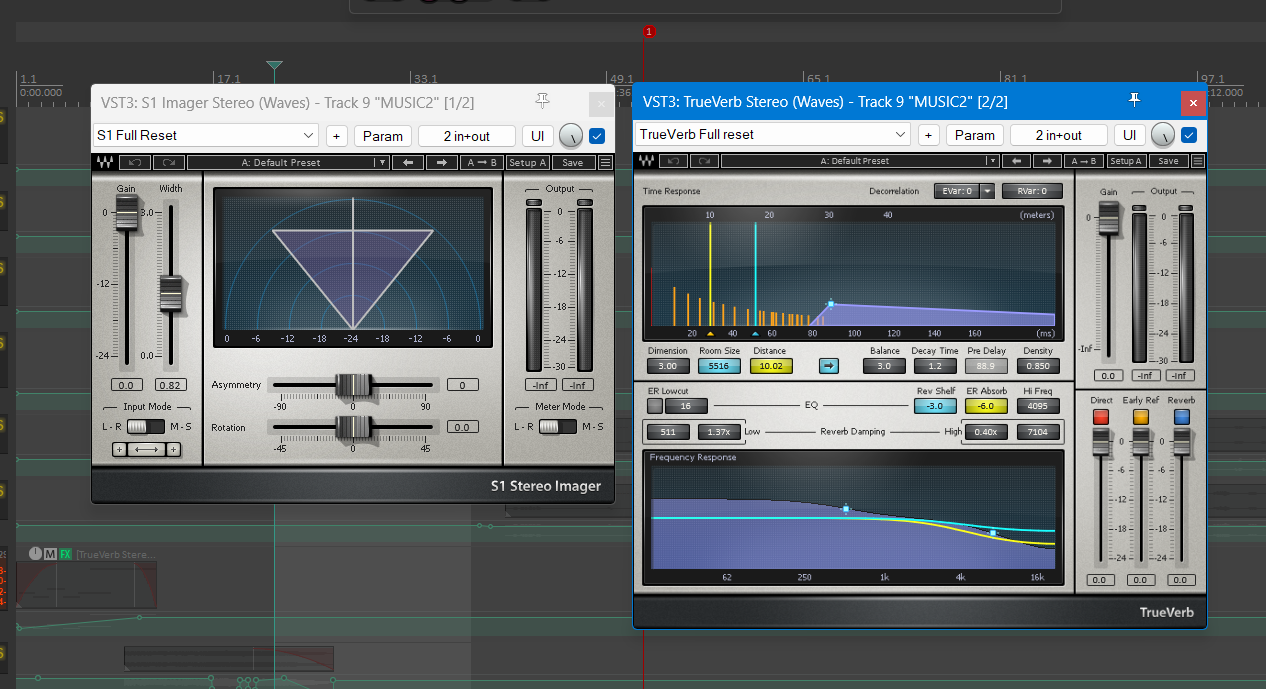

For all elements but specifically for sound design and placement - S1 Imager and TruVerb for sound placement and reverb for environment reflections.

Mastering - Ozone 12 Elements and WLM Meter for final tone / balance and output to specific levels (db and LUFs)

Synths - Polymax, Opal Morphing Synth and GX80